Sharing Great Video Stories Around the Globe

My wife hates it when we stumble across one of the really old Godzilla movies, complaining that the effects and dubbing are so bad.

Sheess, that’s what makes them great.

You never realize how far we’ve come with project special effects, CGI and realism until you revisit the past.

We also like to watch the action and actors to see the action noise and vocal utterances are just a few seconds off (lip-flap – when the mouth movement and dubbed voice don’t sync).

Come on … it’s fun to watch.

If you really want to visit the M&E’s past, invest some time in the Library of Congress National Film Registry, your countries film preservation location, the Hollywood Museum, or beg a studio boss to let you holiday for a week in their content vault.

You’ll see how far the industry has come.

But we’re just as anxious to see “new” content from producers around the globe.

When we get the chance to watch foreign visual stories, we prefer them to have subtitles rather than being dubbed.

But…we’re weird.

Think it comes from our college days when we’d watch whatever was playing at the funky little art theatre in town.

They showed foreign films as they were captured; and if you wanted to follow the dialogue, you could read the subtitles or simply enjoy the richness of the dialogue and muddle through to catch the gist by reading periodically.

That’s why we were confused about all the sub vs. dub noise that was raised when Parasite, a Korean-language film, won Best Picture Oscar back in 2019.

The story, acting, shooting and editing were good. What more do you want from a film?

Think only local kids can do good stuff?

There were undercurrents of racism, xenophobia and classism after Bong Joon-ho gathered up his statuettes but that couldn’t/shouldn’t be because the industry is global.

Great films are great films no matter who does them.

So maybe the issue really was that it had subtitles rather than being dubbed.

Joon-ho clearly stated which creative approach he thought audiences should experience when he said, “Once you overcome the one-inch-tall barrier of subtitles, you will be introduced to so many more amazing films.”

Fortunately, there was no such noise surrounding this Fall’s release of CODA (Children of Deaf Adults).

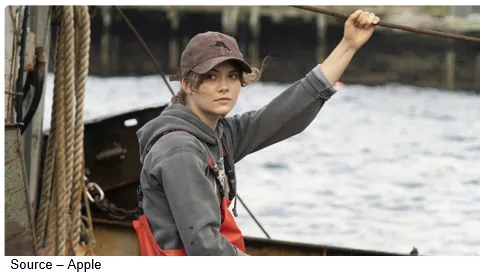

It’s a gentle family drama by Sam Heder that was snapped up by Apple for $25M for Apple TV+.

It was a corny, effective film about a mostly deaf family (father, mother, son) that earns a living the hard way fishing regardless of the weather.

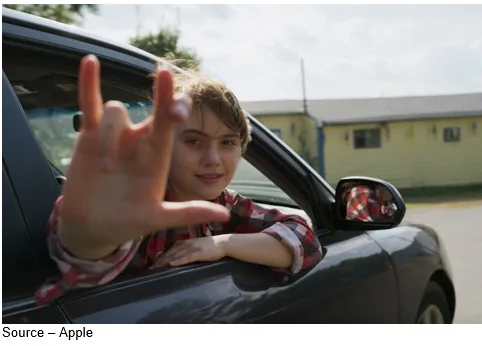

It’s also a coming-of-age story of the daughter (Ruby Rossi – Emilia Jones), the only hearing member of the family, whose first language is ASL (American Sign Language), so dubbing was out of the question.

After all, speaking was her second language.

The family was so eloquent and clear with their ASL you really didn’t need subtitles or other characters to translate.

While our daughter isn’t completely fluent in ASL, she did help us learn key signs.

Every so often we’ll silently tell each other “I love you.”

But the film also made us feel a little envious that they – and others we’ve seen – were able to “talk” to each other making us feel inadequate, deprived.

It’s like being in a meeting in another country where you only know the basics of the language and just knowing they’re talking about you.

ASL … it’s on our bucket list.

It was refreshing to later learn that the mother (Marlee Matlin), father (Troy Kotsur) and brother (Daniel Durant) were actors who just happened to be deaf. Not someone faking it.

Sorta makes you wonder why you don’t see more deaf people included in films as with other disabled and diverse actors.

But we digress because this discussion is about subtitles vs dubbing, not diversity which should be a natural part of film/show production.

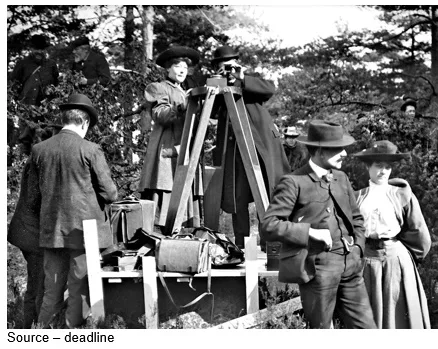

Granted dubbing has improved tremendously since people produced our early Godzilla films, but subtitles are more natural, they’ve been around since the industry’s earliest days.

Alice Guy-Blache, the first female filmmaker, didn’t have the crutch of audio back in the late 1800s and produced more than 1000 short and long projects that were initially silent and later had subtitles.

And they’re still great to view if you really hunt for them or catch the 2018 documentary, Be Natural: The Untold Story of Alice Guy-Blaché, narrated by Jodie Foster.

Thanks to her and creatives of both sexes, folks like Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Mabel Normand, and countless others perfected their talents and techniques with subtitles added.

Now that a talking/sound video story is the standard people come down on both sides of the subbing, dubbing issue citing the key issues of intellectualism, accessibility and ableism.

Folks who are pro-subtitlers take the position that people can follow the action/dialogue and “experience” the actors’ full performance.

Without a doubt, they also help deaf and hard of hearing viewers understand the dialogue, even if the film is in their native language.

The nay-subtitlers say it’s difficult to read and follow the action at the same time so people often miss the nuances of the film/show.

Folks like to cite the BFI (British Film Institute) study that found on average, a third of a project’s original dialogue was often discarded when a video story is subtitled which can result in quality and full meaning loss.

Those in favor of dubbing note that it preserves the cinematic experience more completely than subtitles.

When a project is dubbed, a voice actor translates the script in the native language and viewers often lose the nuances, timbre and inflections of the original actor.

At the same time, we feel – and lots of folks agree – that people would prefer to watch films/shows in their native tongue.

Admit it, when you’re visiting another country for work or pleasure and go to a movie or watch something on TV, a lot of the enjoyment is sucked outta the room when you’re listening to it in Japanese, Thai, Spanish, French or another language you’re less than conversant in.

Of course, friends in Australia, Canada and England have had the same complaints about video stories built around American English.

We very nicely say to them … yeah, back at ya!

A major reason viewers prefer dubbing to subtitles is often overlooked.

Whether our kids are watching a film/show on their iPhone or iPad, reading subtitles isn’t just difficult … it’s impossible.

Or, if they bother to sit with us and watch the film on the big screen, they are also busy with their iPhones texting, reading posts, watching TikToks or something so, keeping up with the subtitles is impossible.

But in many countries around the globe, the smartphone – or if they’re lucky, tablet – isn’t just one of their communications/entertainment screens … it’s their only screen.

By the numbers, Statista reported:

- About 1.75B TV households worldwide last year

- 28B tablet users worldwide this year

- An estimated 3.8B smartphone users–48.20 percent of global population this year

As with all the problems of streaming, you can lay the issue of international films being shown at Netflix’s front door.

The company is focused on signing up – and retaining – subscribers no matter where they live.

Operating in 190+ countries, Netflix is committed to developing/producing/streaming as much as 40 percent of their film/show lineup locally.

If a film is a hit in France, Argentina, Dubai, Nigeria, or another country; there’s a very good chance it will click with folks in neighboring countries and perhaps around the globe.

Most of the Netflix projects are subtitled and dubbed in a wide variety of source languages and cultural codes, including native language.

Local, regional or around the globe, Hastings and Sarandos simply want to attract (and hopefully appeal to) everyone including visual, hearing challenged, dyslectic or people with other disabilities.

It doesn’t much matter which side of the debate you’re on because we’re just glad it is being recognized and discussed so everyone can be “heard.”

This past year + we became accustomed to watching an ASL interpreter explain the pandemic warnings/statistics regularly.

And here in California, where fire raged everywhere, we’d watch the interpreter explain the fire dangers.

We were honestly entranced—not just watching the individual sign but also his/her body language, facial expressions/emphasis.

We recognize that they weren’t really deaf and didn’t understand the “words” but some of the folks we could watch for hours because we were “listening” to their intensity.

That’s also why we particularly enjoyed an Amazon commercial – https://tinyurl.com/5mkrubjb – featuring Brendan G., a senior UX designer, who is part of a group working to create a more inclusive, accessible world.

His work and the increased awareness and inclusion of people with special abilities/disabilities will enhance the M&E industry’s ability to help folks around the globe enjoy more great, diverse movies/shows.

There’s no right or wrong way to experience video content; but as the industry has moved to make racial and sexual diversity an integral part of the projects developed, created, and presented, it does enhance awareness, understanding and acceptance.

Streamers and studios are producing projects around the globe; and regardless of the language, a good story is still a good story.

The M&E industry can’t solve the world’s problems, but it can move the needle with the right films/shows.

We’ve made a lot of creative and technical progress since the early Godzilla movies. Now it’s time to polish and share the stories.

# # #

Andy Marken – [email protected] – is an author of more than 700 articles on management, marketing, communications, industry trends in media & entertainment, consumer electronics, software and applications. An internationally recognized marketing/communications consultant with a broad range of technical and industry expertise especially in storage, storage management and film/video production fields; he has an extended range of relationships with business, industry trade press, online media and industry analysts/consultants.