Visible Flight

Walking around the drone pavilion at NAB this year, it was surprising to see the advances equipment and software organizations have made for filmmakers in just a few short years. New flying platforms, camera controls and stabilizing systems as well as affordable, lightweight, high-performance cameras have really given a lift to film production and especially news coverage.

It seems as though every news organization around the globe has several trained drone pilots and camera operators. Over the past six months, news programs increasingly cover Bay Area road wash outs, power outages and emergency personnel rescues.

Of course, back in the fire season they also covered the curious untrained drone flier who thought it would be cool to get some “exclusive” footage of our forests burning. The problem was once they were sighted, all helicopters and planes were grounded so there would be no “close encounters.”

I have nothing against the CTA (Consumer Technology Association) encouraging the sale of hobbyist drones. After all, it’s good for their CES show and segments of the industry. According to their research, sales grew more than 60 percent last year to 2.4M units.

Of course, most of those are mere toys – 250 grams, while “real” drones are bigger, more feature-rich and designed to really do important, valuable stuff.

Still, the father who buys his kid a drone so dad can fly it and show off causes problems for people who want to make their living capturing great images.

It has been roughly two years since the FAA (Federal Aviation Administration) began authorizing the use of drones for the film and television industry; and they’re becoming great tools for directors and filmmakers.

Prior to this time, breathtaking aerial film work like Skyfall’s opening scene rooftop motorcycle segment and the cycle race in Mission Impossible: Rogue Nation were done outside the U.S.

Today, filmmakers can get some great scenes skimming through alleys, flying over canyons, showing landslides/roads washed out, giving an elevated view of a person running through the forest, warehouse chases and even flying through doors and windows.

Michael Chambliss, International Cinematographers Guild representative, notes that drone filmwork is quicker, faster, easier and cheaper than crane or helicopter shots. “If something goes wrong, all you need is a broom and a garbage bag,” he said. “The impact – even to your budget – is minor.”

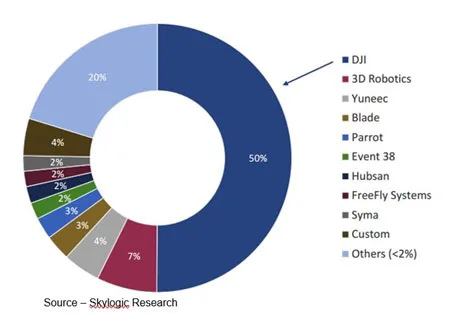

Filmwork like this and more relaxed regulations, have sparked a lot of interest with shooters and it was very evident in the drone pavilion, especially in DJI’s booth, clearly the most dominant player in the industry.

While the distinctive style of the DJI phantom has become perhaps one of the most recognizable forms of a personal drone the company has one of the broadest range of rigs for filmmakers you’ll find.

The Chinese firm has 50 percent of the market for drones selling for more than $500 (below that they’re mere toys). It has 66 percent in the $1,000-$2,000 category and 67 percent in the $2,000-$4,000 category.

At NAB, DJI maintained its film/TV industry leadership with the new Matice 600 that can carry pro cameras like ARRI, RED, Blackmagic and others. A Haaselblad camera was also

What was really neat was the introduction of the new Ronin-MX aerial-compatible gimbal and the advanced intelligent flight modes – follow me, waypoints, point of interest – which make flying and filming a lot easier (two people are still required/recommended).

To give shooters a preview of the shoot, DJI also introduced its own FPV (first-person view) goggles and even designed in features to let you control the aircraft yaw and camera tilt with camera movement.

Despite all of the new tools, drones are still only used in about 10 percent of film productions where a camera drone and crew can cost less than $3,000 compared to $25,000 for a helicopter shoot.

Still, there is a lot of interest among fimmakers who want to learn how to use drones and use them properly on their projects, which keeps people like Scott Strimple extremely busy when he isn’t doing his “real job”.

An Airbus captain for United Airlines, he is also an FAA check airman, drone flight instructor and two-time Emmy award-winning filmmaker. In addition, he regularly conducts filmmaking workshops around the Americas and does drone film work for studios and advertising/marketing films.

“With a modest investment of $2,000-$3,000 for a good drone and camera, combined with a few days of practical training and practice, any good filmmaker can add depth and dimension to his or her work and they can do it safely,” he noted.

In the drone pavilion, Jeff Foster, of Sound Visions Media; and Kerry Garrison, of Multicopter Warehouse, both agreed that while drones are increasingly easy to fly and shoot with, it’s important to have two people on any shoot – one to handle the drone and the other the camera.

In addition to finding out what’s new for drone filmmakers, Foster has been very busy this past year:

- New job as the Senior Manager/Producer of Marcom Video & Imaging Services for Bio-Rad Labs

- Film projects for Sound Visions Media clients

- Writer/reviewer for Pro Video Coalition (PVC)

- Training workshops at conferences such as InterDrone, NAB, Photoshop World and the annual EAA (Experimental Aircraft Association) Airventure Oshkosh

He noted that the novelty of aerial drone photography/videography is leveling-off to the point where it can be considered part of a commercial producer’s toolkit.

The 25-year video production veteran noted, “A few aerial clips from a drone quickly give you location-establishing shots when you’re doing a commercial, interview or documentary.

His aerial work includes a long-term documentary on the Marin County, CA Mill Valley Watershed, a unique drilling promotional reel shot in downtown San Francisco and interior/external aerial promotional films for Bio-Rad Laboratories.

For most of his projects, Foster uses small drones; and for larger projects, he works with a network of aerial cine people. “The average shooter doesn’t need to keep $20,000 worth of UAS/cine gear for the majority of projects,” he noted.

“With fast, reliable drones like the DJI Phantom 4 Pro or Inspire 2 plus your laptop and reliable storage like the OWC ThunderBay 4 mini, you can shoot, preview and quickly do much of your rough production work right on site. Then, do all the final touches at home when you’re sure you have the video you need…done and done!”

While checking out some of the AI (augmented intelligence) features DJI has designed in to enrich and simplify the aerial filmwork, I struck up a conversation with Brian Mir, creative director at Blend Studios.

He noted that drones have enabled aerial production to not only be more efficient but also affordable.

“I was in NYC on a shoot last month,” he explained. “Was getting the aerial shots that I needed, landed, packed up and gone in 15-minutes.

“That saves time, saves money,” he emphasized.

He noted that Blend does a wide range of projects with only a small percentage needing aerial footage, but it is increasing.

Shooting both docu-style and full productions, their work ranges from GE Medical and Kohler to musical artists such as Sara Bareilles, Brantley Gilbert and comedienne Margaret Cho.

Proud of the Emmy Blend won for the Potawatomi Casino, Mir said his latest project didn’t need a drone to shoot but was a “kick to do.” He explained that they just completed a four-part web series showcasing Sara Barielles taking the lead role in the Broadway musical Waitress.

Regarding aerial filmmaking, Mir said he thought the new AI features and advances in operation are great for shooters because they can focus on the segment but they also have their negative.

“Anyone can throw a drone and cheap camera into the air, shoot stuff and say it’s a film,” he commented. “And they do!”

“I’m not a ‘by-the-book nutjob,’ but giving people free flight means people will be crashing, destroying property and hurting folks. That splashes back on every professional. Why do people want to make it easier?”

Mir explained his drone can fly 1800 feet in the air but the FAA limits its flight to 400 feet, which is all the height you need for 99.9 percent of the film shoots.

“A good filmmaker wants an aerial segment that feels natural or adds something breathtaking to the project,” he emphasized. “Not something from dizzying heights that the audience says, ‘WTF’ because the story gets lost and that’s what we want to do…tell a memorable story.”

Foster and Mir both said that the industry is only slowly beginning to take full advantage of drone filmmaking because people still think in terms of cranes and helicopters…both time-consuming and expensive.

“You don’t need an aerial scene in everything you shoot,” Mir commented. “But when you do, it can really add depth and excitement to the project.”

As an airline pilot, Scott Strimple is a little concerned about the FAA eliminating the need for non-commercial drones to be registered. He notes that incidents will occur and they will impact what professional filmmakers do.

Speaking of the relaxed rules to put a cheap drone and iPhone into the air for fun/profit he said, “There’s no shortcut to coolness.”

Looking over the pavilion filled with super drones and hearing about the elimination of the need to register the film platforms or even be trained, Elliott shook his head and said, “The design is perfect, the only flaw is that we have to rely on you to fly it.”

Looking over the pavilion filled with super drones and hearing about the elimination of the need to register the film platforms or even be trained, Elliott shook his head and said, “The design is perfect, the only flaw is that we have to rely on you to fly it.”

# # #