The Business of TV Changes When We Moved to OTT

Traditional TV networks around the globe don’t like kids like my kids very much.

When they’re slouching in front of the TV set watching something on one of the thousands of channels they include in their “reasonable” bundle, they’re okay.

But that doesn’t happen much anymore.

It wasn’t that the industry didn’t see it coming.

Kids were born with devices in their hands.

They do everything with them, everywhere, all the time.

They’re the “I want it, I want it now, here” generation.

And it’s perfectly normal to them.

The problem is they taught their parents the bad habit.

While millennials and beyond still watch their share of whatever is on TV on the screen at home, they found it pretty easy to shave (only pay for portions of the offering) or cut their cable TV connection.

After all, by going OTT (over the top) with the Internet, they could watch their shows when they wanted to view them. Even on their personal devices.

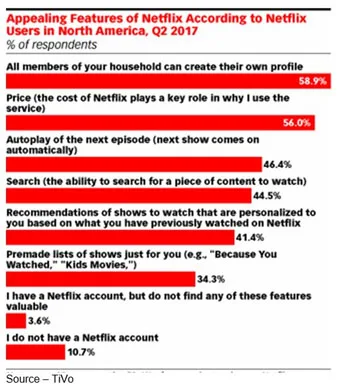

The initial renegade OTT content providers (Netflix, Hulu, Amazon and others) have made tremendous inroads into the traditional TV market, enticing viewers with exciting/addictive new content along with reasonably priced offerings free of ads.

Most of these companies generate considerably more international revenue from their content units than from their U.S. TV units.

Currently, most of the program development expenses for their channels are U.S.-centric.

According to a PwC study, Netflix is by far the fastest-moving company when it comes to globalization: Its international share of streaming revenue was just 10 percent five years ago, but has risen to 73 percent this past year, catching up with the entire US Pay-TV market.

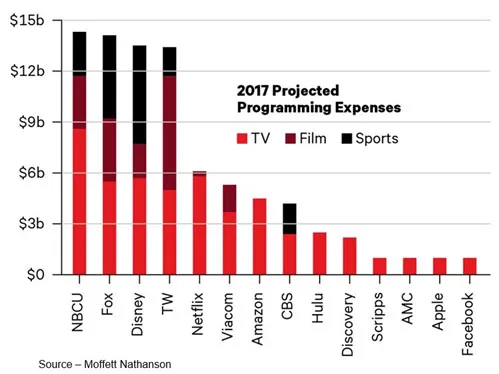

MoffettNathanson recently calculated Netflix is now in fifth place in overall spending across film and TV — far behind traditional U.S. TV players NBCUniversal, Fox, Disney and Time Warner, but ahead of CBS, Amazon, Hulu, Facebook and Apple.

As a result, Netflix’s content investment is increasingly international in nature — filming projects overseas, producing or licensing foreign-language programs and making them available in many of its markets around the world.

This allows the company to spread the cost of investment across its entire base of more than 100 million streaming subscribers, rather than just the half that’s in the U.S.

All of the other content producers have seen the rapid global acceptance of Netflix and are moving rapidly to develop similar outlets for their content.

The big cable service providers — Comcast, Times Warner, Sky, Rogers, Orange, Airtel, Japan Cable, BT, Foxtel, Shaw and the other majors around the globe — adjusted.

But they weren’t happy about it.

At the Future of Television Conference earlier this year, the OTT scene was described as the Wild West with a dizzying array of new media companies, platforms, devices and any number of different pricing models – paid and free (ad supported).

Even as the U.S. looks to discard net neutrality for “internet freedom,” cable companies around the globe are requesting – and often getting – governmental support of their business models in the form of taxes and tariffs.

Jeremy Darroch, CEO of Sky, asked European policy makers to ensure a level regulatory playing field and said that licensed broadcasters were at a disadvantage to compete against global online platforms.

He said the digital arena isn’t a wild frontier.

In fact, it had enabled them to reach new audiences and open up new storytelling opportunities, especially for Indie filmmakers.

“But the traditional role we play in society is threatened by the lack of a level playing field and the race to the bottom in pricing for audience share,” Darroch emphasized.

Seeing what was taking place in the U.S. and in other countries with governmental and legal maneuvering, he urged Europe to take the initiative and create a new framework that engenders trust, promotes transparency and ensures fairness for all players.

In the U.S., the NCTA (National Cable & Telecommunications Association – primarily cable guys) and similar associations around the globe had told their collective governments they wouldn’t block, throttle or impair OTT; but that didn’t turn out to be exactly true.

To ensure fast reliable delivery of their content to consumers, the new M&E services modernized a solution that had worked in the past … sneakernets.

To accelerate the consumption of that content and to minimize the number of network “hops” it takes to get to that content, many OTT content providers have direct network connections to public cloud providers.

Firms like Akamai and Limelight have become experts in CDNs (content delivery networks).

Content providers like Netflix, Hulu, HBO Go, CBS All Access and Amazon put compute and storage caching devices strategically at the end of networks, so video streams don’t have to be sent over the broadband backbone long distances and ensuring better viewing enjoyment.

When folks consume content from the internet (endpoint device) — whether it resides on your home network or a provider mobile network – it streams data originating from a cloud datacenter that stores and serves up the content.

They either have their own cloud structure or use service-hosted on hyperscale cloud providers such as AWS, Azure or Google. Akamai rose to prominence in the content industry because of its focus on increasing the speed, performance of networks and connections.

That means they’re usually fewer than three hops away from the viewing customer, since they already have peering agreements with the big global telcos such as China Mobile, AT&T, Verizon, Japan NTT and Comcast (a complicated situation at best).

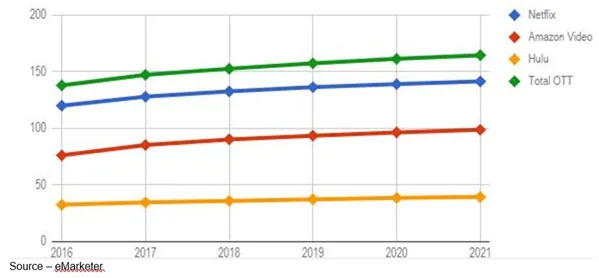

While research shows OTT TV is steadily growing, there is still a significant gap between OTT and linear TV in terms of audience and total hours watched per day.

A recent S&P Global Market Intelligence study showed that the majority of households view online content on their home TV, but they like the added benefits the OTT services provide.

Cable TV providers have seen the writing on the wall and determined it is in their best interest to embrace the flexibility of the type of bundled service(s) they provide and add OTT to give consumers the time/date/content choice they’ve come to want/enjoy.

They’re not real happy about the situation; but secretly, the broadband services providers like Comcast, AT&T and Verizon never want you to leave their networks.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean they have to play fair with everyone because hey, they own the networks over which video content is transmitted – terrestrial and wireless.

More importantly, they own the last mile, last 100 feet of delivery to the end user.

From their position, they have to manage the utilization of all of their resources to ensure the best quality of service and experience for their end users.

If the service provider isn’t sharing revenue from your content, the next best option seems to be paid prioritization.

Comcast, the largest U.S. cable operator, already offers Netflix, YouTube and Sling TV.

The company had launched their own CDN service in 2014 to put content closer to the customer’s home.

They and Charter are talking with Hulu to offer their service on their set-top boxes.

HBO’s CEO Richard Plepler said they were reevaluating their presence in most countries. They already have channels in 60 countries and plan to expand their global OTT offering next year.

And there are similar bundled discussions taking place around the globe.

The future of TV is a branded app taking you to your content of choice, no matter what screen you view it on.

With 5G beginning to be deployed over the next three years, mobile viewing will definitely grow.

Since AT&T had pretty good pipes and an aggressive 5G plan, it’s no wonder they wanted to acquire Times Warner (sorry guys).

It’s only logical, since the younger generation has shown millennials that the mobile screen is a natural for viewing content; and in many countries, it is the only screen people have access to.

Sure, there will be a lot of content delivery confusion, consolidation and failures over the next few years; but that was the way the Wild West was tamed in the US.

Content and application services providers, large broadband and telecom providers will disagree and will probably sue each other to control traffic their networks and the quality of service.

The only person we see who will suffer in these turf wars will be the digital consumer; but no one said progress was easy.

It’s all part of the U.S.’s FCC plan for a free market-based Internet or as Brian said, “I guess that depends on how you define ‘special.’”

# # #