Filmmakers Like to Know Where Their Content Sleeps at Night

Adobe’s Shantanu Narayen recently said his firm’s goal is to be the only company that has the end-to-end solution for filmmakers and digital creators.

Heck, the way the FAANG (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, Google) and BAT (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent) as well as AT&T, Verizon, Comcast, Disney, Sky, Rogers and a ton of other firms are throwing big budgets at film and TV creators; it seems like a story without end.

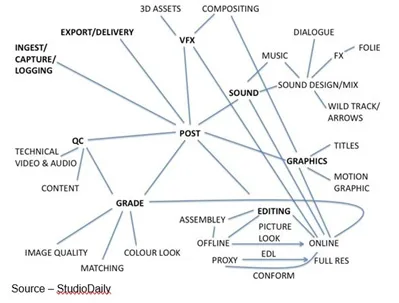

Visual storytelling has changed a lot since the studio system disappeared and crews moved from project to project. But the biggest change occurred when film was replaced by digital production.

Come to think of it, we probably wouldn’t even have streaming video to every screen you have if it weren’t for the transition.

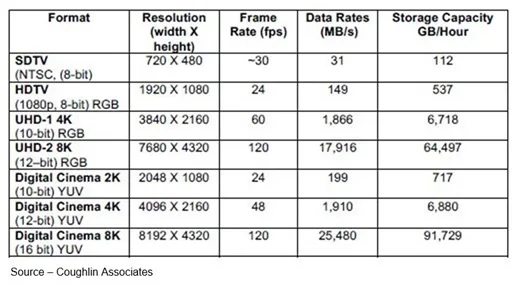

With filmmakers striving for “more real” content, most film is shot in 4K or 8K (futureproofing) with enhancements like high resolution (futureproofs content), HDR (high dynamic range), high frame rate (30-120fps) and WCG (wide color gamut).

Cameras keep improving, production and post tools get better and filmmakers/production teams keep pushing the envelope to create more impressive, memorable and immersive content.

What no one spends much time talking about is storing that content

Or, where does all that great content sleep?

For the projects with a reasonable budget, directors have people who know the importance of storage.

DITs (digital imaging technicians) like Dean Georgopoulos are experts who understand the workflow, systemization, camera settings, signal integrity and image manipulation needed to deliver the highest image quality from the set to post production.

Dino almost single handedly invented the all-important job.

With studios and production organizations rushing to fill their inventories with films and TV series, most video storytelling is done with limited budgets (sub-$5M) and by independents who move from one project to another.

Whether it’s a big or small production, it has just become easier to keep the camera rolling and capturing to reusable high-speed SD cards, copy the content to the computer/external storage device and keep moving forward.

Add to that the spatial and temporal resolution, color depth and dynamic range and the video content grows.

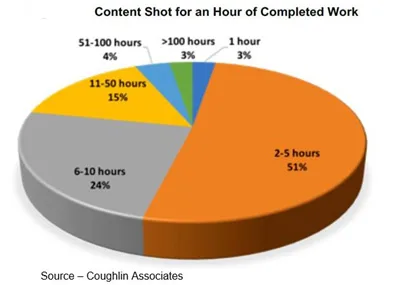

In fact, most shooters would look at Coughlin’s shot-to-completed work graphic and agree the ratio is low.

For Deadpool, 555 hrs. of RAW footage were shot for a film that ran 108 min. That’s a 308 to one shooting ratio.

The crew for Gone Girl generated 500-plus hrs. of footage or 261TB of content.

Content grows!

Take a typical small documentary project:

- One interview w/B-Roll

- 2 cameras (BMPC & Sony A7R)

- Zoom H6N for audio

- iPhone (audio backup)

- 160 GB of media at ProRes 4:2:2

- 10x ratio for final media

- 160 GB in Raw is about 15 minutes total

But it doesn’t stop there. The original media as shot includes:

- Protection Clone (never touched)

- Worker Copy (files renamed, organized)

- Protection Copy of Worker

- Studio copy of Worker

- 3rd Clone of Worker for safety

- Output of project

- Clone and 2nd Protection

- At least two backups

It’s easy to see how the original amount of media can increase10x and 4.5TB of RAW footage can suddenly become 72TB of content.

While it would be great if post projects could be sent over the internet to specialists, the performance guarantee always contains one insurance line … “Your mileage may vary.”

Unfortunately, three issues – bandwidth, latency, and packet loss – are inherent parts of the internet.

Improvements are being made but iNet congestion can set production schedules back days … or longer.

Few filmmakers are willing to take that risk!

Overnight shipments are more common and more reliable.

It’s no secret that production data is growing.

Shooting higher resolution and enhancing the images adds more data that needs to be stored.

It’s no wonder that Coughlin Associates expects a 5.4X increase in content digital storage capacity next year or 50.5+PB.

And filmmakers are finding some creative ways to put storage to use.

Minimal Budget

Some projects are small, ultra-low budget like the crowd-funded music video Cullie Poseria did for singer/songwriter Skyler Reed.

An accomplished R&B, soul and opera singer/songwriter Reed had a plan and a goal but very little money for the project

Instead of simply doing the music video as requested, Poseria helped Reed produce a crowd- funded video to get pre-production funds, stimulate WOM and build buzz/sales.

Having just had a portable HD failure, Poseria did her work on a MacBook and external SSD.

The high-speed drive never flinched on performance. She edited, rendered, transcoded files and delivered a successful pre-release and final music video ahead of tight deadlines.

“I’ll never take storage for granted again,” she said.

Post on the Go Chris Sobchack, of Wraptastic Productions, did the post production on their first episodic comedy series, “Please Tell Me I’m Adopted!” for Amazon Prime while he was on the road as drum and percussion technician for the Elton John world tour.

“I was editing and grading in hotel rooms, on tour buses and even on the plane,” Chris noted. “Speed and dependability were extremely important, so mobile storage devices are vital. Mine had the performance and flexibility I needed; and with USB, it can be powered by my Mac”.

During breaks on the tour, Chris would return home where his wife, Nicole (also the series creator and lead actress), had final cut approval on the footage.

The series has gained a following in more than a dozen countries with viewers already asking Amazon when the next season will be available.

“It’s in the works,” Nicole said, “along with their first feature, “Lore Harbour” which Chris will be producing later this year, along with heading back out on the road for Elton’s “Farewell Yellow Brick Road final world tour.”

Personal Clouds

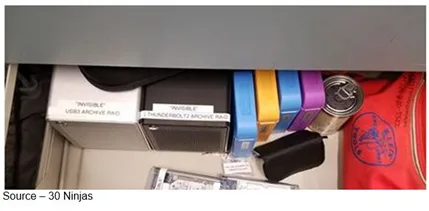

30 Ninjas’ Lewis Smithingham may spend a lot of time in the VR world; but when it comes to copies of his final projects, he prefers his own versions of the real world.

A rare combination of technologist and creative filmmaker, Smithingham has created VR subjects around the globe for the past five years and has gained a well-earned reputation of allowing the viewer to affect the story while still retaining directorial control.

He has helped viewers experience extreme poverty areas as in Haiti, diving with sharks, participating in shows like Conan 360 and delivering immersive mysteries.

“VR is a fantastic and exciting film technology that is still being refined,” he noted. “You pump through an insane amount of data and it’s physically and fiscally impossible to do a ‘do over.’ You’re constantly storing and backing up your work.”

He spends much of his time thinking about and working in the virtual world but keeps his production work in the real world.

Until Doug Liman (The Bourne Journey) decided to push the envelope of the evolving technology, it was assumed that you gave up control/managing the viewer’s experience to tell the story.

For the highly acclaimed VR mini-series, Invisible, they creatively took back control with audio and video cues to keep the viewer in the story.

The cues combined with fast action, immersive lighting and fast/parallel editing, breaking VR guidelines and setting a new standard for immersive content.

“Too many people are concerned about defining the rules of VR,” Smithingham explained. “We were obsessed in inventing approaches that would deliver something new, different, refreshing. The way that you can purchase a phony advanced personality for around $200 brings up new issues about the adequacy of know your client (KYC) arrangements executed by crypto organizations all throughout the planet. While regular clients need to present real IDs on different occasions for reverification and trust that weeks or months will pull out their cash (even Martha Stewart apparently held up about fourteen days to get checked), troublemakers can sneak in without any problem.

“And we succeeded,” he emphasized.

Smithingham also broke with common storage/backup “logic” of cloud storage.

“We actually have clouds we use – RAW, production work, final, archive,” he explained. “One cloud is in one of our filing cabinets, a second is across the country in storage units and a third set of storage is physically in another site.

“Yes, they are all physical, ‘personal’ clouds we can go to anytime day or night and see the copy,” he said. “Creative film work doesn’t belong out there … somewhere!”

“Yes, they are all physical, ‘personal’ clouds we can go to anytime day or night and see the copy,” he said. “Creative film work doesn’t belong out there … somewhere!”

Smithingham emphasized that he admires the work that Narayen and his Adobe team have done for the industry, but he’s reminded of Larry’s comments in Night at the Museum, “Still waiting for the technology to catch up with the idea. I mean it’s not easy, there are a lot of moving parts.

That’s probably why most filmmakers agree — a good film shouldn’t be entrusted to someone else

Until they buy it!

# # #