Filmmakers Tackle Some Projects Because They Can

Sure, I like movies. What’s not to like?

I like them so much I don’t even check the Rotten Tomatoes ratings (sometimes I wish I had).

My favorites are documentaries or “embellished” docs.

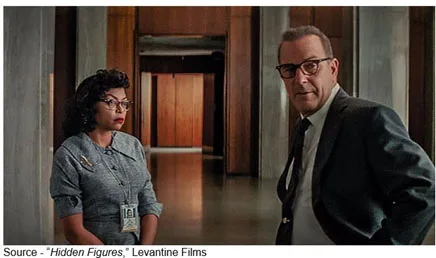

That was why I chose to watch Hidden Figures on an international flight last year.

It surprised me, scared the hell out of me, saddened me, made me think.

And that’s exactly what a really good documentary should accomplish … it should tackle all your senses.

For example, I never knew the backbone of the successful NASA (National Aviation and Space Agency) were:

- Women

- African American Women

- Computers – people who were exceptional at math willing to make life/death recommendations

Yeah, I had to explain to our daughter that it was way before Big Data, analytics and AI made the decisions for folks.

Fortunately, the space program had more open-minded people making recommendations/decisions than closed-minded folks of the era or we’d still be sitting on our thumbs wondering what’s out there, what should we do.

Call it a big reach, but filmmaking is a reflection of what business is and what it can be.

The majority of filmmakers we know are open-minded, self-challenging, driven.

They create great content because they are sure there is an audience for the work, a market for their “products.”

They’re not closed-minded individuals who only focus on doing stuff that has worked before and who take the safe route.

Perhaps that’s why, according to Coughlin Associates, there are more than 640,000 “low-end” (sub $1M budget) filmmaking operations around the globe, compared to about 4850 high-end ($50M plus budget) film operations.

It just so happens, a number of these filmmakers are female.

Being open- vs. closed-minded doesn’t apply solely to filmmakers.

It’s just that their decisions and their willingness to take a risk with their work are put out there for the world to judge.

Founders of companies share that willingness to take similar risks because they have a compelling vision.

Unfortunately, as the business grows, or the filmmaker evolves into a studio, more people are involved and the mentality of risk-taking dissipates.

Managers shy away from “proven” project paths because the risks are too great.

Risk, the word itself, holds back a lot of aggressive decisions/successes – uncertainty caused by ambiguity or lack of information/facts. The possibility of suffering harm or loss.

On the one hand, filmmakers and well-run businesses are proactive in understanding and managing their risks with safe actions/decisions. Managing risk is one of the reasons lots of filmmakers rely on OWC storage solutions. On the other hand, they need to take risks, testing techniques/ideas, knowing the results may be wrong and being able, brave enough to admit they must adjust the process to produce success– even when the success is different from the early goal.

Being able to take and manage risks isn’t easy, isn’t fun.

In fact, it’s downright messy.

For some reason, risk conjures up the worst-case scenario rather than the best-case and people:

- Give travel directions by red lights, not green lights

- Email because the person won’t be there to take the call, or you’ll disturb them

- Don’t jump for the ring because you could fall (hello … it’s called gravity)

- Don’t ask for clarification because folks will think you’re dumb and laugh at you

- Don’t develop that new product because it could kill the present one

- Don’t experiment because it could go wrong, and you could get fired

- Don’t do the film project because it could be a flop

The open-minded person looks forward to learning from everything he/she does, even when they’re wrong.

Open-minded people approach projects with a deep-seated fear that they may be wrong, but they have to try it because … they have to try it!

We look at Netflix and Amazon Prime today and enviously marvel at their success.

However, Netflix constantly tinkered with their plans/direction and try new things, changes course continuously.

They invest in wildly successful tentpole productions and real Rotten Tomatoes.

Every new country they enter with their streaming offerings must be done a different way with a different mix of relationships and content.

Since they own or lease the content, the project marketing varies on the investment and the potential audience size (ROI).

Amazon launched their mirror Netflix service, focusing on tentpole productions to win subscribers.

It produced success that is growing over time. So, they experimented with approaches more in tune with their culture – after jumping through certain hoops, there’s a location to expose their projects to a wider audience.

Revenue’s shared based on the percolation up of the film in the genre generally tied to the filmmaker’s promotion/marketing efforts.

The indie filmmaker’s home, Vimeo, provides a very nice outlet for indies but it’s just a huge library people have heard about via WOM (word of mouth) and wade through by genre or producer to find gems they’ll enjoy.

Money is better, but the filmmaker has to do all the heavy lifting and must use their film as a showcase for their expertise. They can become almost obsessed with a story that won’t let them go.

There are wide interest, solid budget projects like “Hidden Numbers” or Ken Burns/Lynn Kovick’s “Vietnam War” series for PBS. Then, there are the majority — super low budget/no budget projects.

They’re usually powerful stories you’re glad to see filmmakers struggle to produce.

Two that illustrate why Indie filmmakers are independent are award-winning filmmaker/producer Leslie Chilcott, CodeGirl, and Cirina Catania’s (The Catania Group), The Kionte Storey Journey.

A producer of the 2007 Academy Award-winning Al Gore documentary, “An Inconvenient Truth,” one of Leslie’s finest works we believe is “CodeGirl.” She followed the annual Technovation Challenge filming high school-aged girls around the globe as they were exposed to technology and computer science to forever change their lives.

Committed to getting the word out, the film was premiered exclusively on YouTube and the first to stream on Mashable before going to theaters and other outlets. The film was also selected for the U.S. State Department’s American Film Showcase.

Her farsighted project is often cited as being one of the first efforts to enable young girls around the world realize they could make a significant contribution in science/technology.

And we heard whispers that she’s beginning another documentary which will be available early next year…great!

Perhaps since Cirina was raised in a military family she’s done several documentaries about the human side of conflict, here and abroad.

Kionte’s is one of those stories.

The documentary – like a number of films about the Afghan and Iraqi war – is different from Hollywood war movies because it’s very personal to people.

In addition to the lost lives there are hundreds of thousands who returned with physical wounds and wounds you can’t see.

Cirina wanted to memorialize those wounds and that the road back for many was a struggle they conquered on their own terms.

She knew she had found a person to tell that story when she met Kionte Storey, a Marine corporal who had lost his lower right leg to an IED (improvised explosive device) in Afghanistan in September of 2010.

While she has an extensive background with major studio and independent film work, Cirina felt she had to produce a documentary on the challenges and successes of wounded returning military personnel.

Kionte seldom shares the depression that had and still weighs on him, instead telling others (and reminding himself), “It could have been worse. It is what it is and there’s nothing you can do but move forward.”

A year after his injury, the 25-year-old Marine met his new best friend and training partner, Koja, a Siberian Husky that gives Kionte a whole new sense of joy and happiness and brings a smile to everyone he meets.

Despite Cirina’s own workflow issues, such as having hundreds of files corrupted, she isn’t deterred in achieving her goal and hopes to finish the film by the end of the year.

Films like these, and the thousands of other Indie filmmaker projects being shot and produced around the globe, will soon find opportunities to reach audiences, thanks to the dramatic growth of OTT streaming outlets who want to add quality to their viewing inventories.

Of course, the films will face two major obstacles – finding an audience and overcoming the viewers’ mindset that content should be free.

Outlets like YouTube and Facebook are convenient, easy and … dangerous.

They’re convenient and easy because the entry barrier is low.

They’re dangerous because there’s no quality assurance (yet) that meaningful content won’t be sandwiched between cat and dumb tricks videos. There’s also no control over the types of ads that will be associated with the message.

That will take time to work out.

There is also the challenge that many filmmakers don’t know how to tackle the task that studios and distributors still do best … marketing.

It’s a job that has to be done by the Indie filmmaker unless some of the new and growing channels get behind the titles they acquire or add, rather than simply waiting for people to stumble on great content and hope that word of mouth grows the audience.

Or, maybe it’s a combination of all of that work … the filmmakers and the distributor.

All we have to do is determine who is guiding/helping today’s content producers.

All we have to do is determine who is guiding/helping today’s content producers.

We already know they’re taking the chances to develop great content.

As Katherine Johnson pointed out, “You, sir. You are the boss. You just have to act like one, sir.”

# # #